The following is an edited excerpt of a longer article. Please contact us for a copy of the entire article.

Watch any cable channel and invariably it has a segment discussing how President Biden’s job approval rating and the voters’ views on the direction of the economy are underwater. Yet ask any White House official, and in particular the current Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, and their answer is that Bidenomics is working, just look at all the positive economic data, and that the abysmal ratings reflect a messaging problem.

But what if instead of messaging, the issue is Bidenomics? How would we go about finding out? To find out we borrow a page from when President Reagan ran for office in 1978. He asked the voters a simple question, “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?”. He knew the answer to the question. It was contained in the famous Misery Index, the sum of the unemployment rate plus the inflation rate. Since then, millions of voters have used these simple measures to determine whether they are better off than they were four years earlier. Although more nuanced today the issue is the same. Are we better off today than we were under Donald Trump up until the point when he shut down the economy?

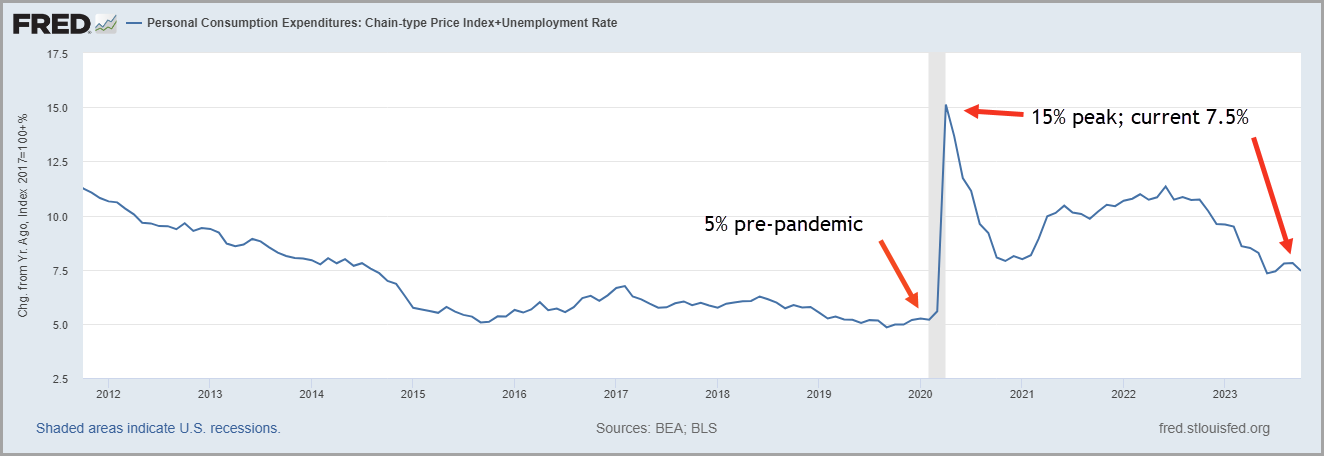

Figure 1: The Misery Index: PCE (Inflation) + Unemployment

The Misery Index verdict, Figure 1, provides a simple explanation for President Biden’s dismal job-approval ratings. The Misery Index stands at slightly below 7.5% while prior to the shutdown the Misery Index stood at nearly 5%, suggesting that the economy is worse off today than it was prior to the economic shutdown.

Even if the Misery Index is correct, will the Biden administration change course? We doubt it. The policymakers within the Biden administration have a strong degree of conviction in their economic view and as a result are unwilling to change it even if the data suggests that a change is in order. We attribute the strength of the belief to the stock market’s success, to “Obamanomics” and Obama’s reelection to a second term in spite of facing what appeared to be dire conditions at the end of his first term. The parallel has not escaped the Biden administration.

In a very interesting Op Ed in the Wall Street Journal, “A New Approach to Taxes That Pays Its Own Way”, Brian Deese and David Kamin (“D-K”) outline a second term Bidenomics fiscal policy trojan horse. Let’s focus on the framing of their approach.

“The tax system of the 1990s could have financed the government we have today. But two decades of successive unpaid for tax cuts eroded our nation’s revenue base. Without those tax cuts, federal debt as a share of the economy wouldn’t be projected to rise significantly over the coming decade.”

The previous statement should be challenged on several counts. First, even if everything the authors say is true, the last time we checked, the deficit is the result of the difference between government spending and revenues. The above quote only addresses the revenue side. But what about the spending side? It is obvious that some spending restraint would have reduced the cumulative deficit. Yet spending does not seem to be an issue of concern to D-K.

The statement also suggests that absent the tax rate cuts the nation’s revenue base would be much higher. A reduction in tax rates reduces the amount of revenue collected per dollar subject to tax, hence the revenue base effect that the authors mention. This ignores the possibility that the lower tax rates increased the incentives to work, save and invest, thus resulting in more dollars subject to the now lower tax rates. The latter is nothing more than the so-called supply side or substitution effects.

A fair reading of the D-K article suggests that they assume these substitution effects are insignificant or nonexistent. Doing so greatly simplifies all the revenue estimates of tax rate changes. The revenue effects will simply be the product of the tax rate times the appropriate tax base. The static analysis assumes that the tax rate changes have no impact on GDP other than the tax effects on disposable income and government spending effects on aggregate demand. The assumption of little or no substitution effects also reduces the upside.

Another implication derived from this analysis is that if there are no substitution effects, then up to a 100% tax rate, there is no limit to the amount of taxes the government can impose on the economy. Under the assumption of little or no substitution effects, once the government sets its spending priorities, all it needs to do is set the tax rate to raise the requisite amount of revenues based on the static revenue analysis. In fact, that seems to be the implicit assumption behind Bidenomics 2.0. But, if substitution effects are significant, the federal government will be sorely disappointed as the static revenue estimates will fall short of the amount collected by the tax rate increase.

The possibility of large substitution effects does not dissuade D-K whose proposal, if enacted, would introduce an upward bias to the tax code in order to finance greater Bidenomics expenditures.

“The good news is that there are tax reforms that would raise significant revenue, strengthen the tax base and promote economic growth. For starters, corporate tax reform can raise hundreds of billions over the coming decade while encouraging investment and innovation. The 2017 corporate rate cut was particularly ineffective at sparking investment. It handed out windfalls to old investment instead of targeting new investment, and the law allowed too much unproductive offshore profit-shifting to continue. Americans can do better by focusing on incentives for new investment and by raising the tax rate on foreign profits in line with the global minimum tax agreement.”

There is no mention of what taxes D-K would reduce, apparently none. Nor do they discuss the possible disincentive effects that the different tax rate increases would have. None of this is surprising given their implicit assumption that the substitution effects are small. This then brings us to the asymmetry in the pay as you go system they propose. Tax rate reductions have to be paid for but spending increases do not. There is no discussion about tradeoffs among different expenditures. The presumption is that tax rates will increase to cover these added expenditures. The authors leave no doubt about their intentions.

“Given the magnitude of our fiscal challenges, we ultimately will need to raise revenue beyond paying for tax-cut extensions in 2025 and address other salient fiscal challenges, such as continuing to slow the growth rate of healthcare costs. But the greatest near-term fiscal risk the country faces is the possibility that policy makers won’t only extend the 2017 reform, but double down on these unpaid-for, regressive tax cuts. Doing so would deal a huge blow to market confidence and the economy. Tax cuts now would likely come at the expense of long-term growth and American pocketbooks.”

The previous paragraph contains two important promises. The first one being that if President Biden gets reelected, a continuation of Bidenomics requires an increase in government spending during the second term. All of this suggests an increase in the degree of government intrusion in the economy. An increase in economic dirigisme. The second and equally disturbing suggestion being the warning against “doubling down” on the 2017 tax reform. This is not surprising coming from someone who does not believe that the substitution effects are large. Hence, they do not believe these rate cuts will stimulate incentives to save work and invest. But are the substitution effects really as small as D-K believe?

A look at the empirical evidence suggests not. A recent column, “The Trump Corporate Tax Reform Worked”, by James Freeman of the Wall Street Journal, offers an interesting rebuttal to the D-K hypothesis.

“Economists from Harvard, Princeton, the University of Chicago and the U.S. Treasury report in a new National Bureau of Economic Research paper on “the investment and firm valuation effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, the largest corporate tax reduction in the history of the United States.” The authors share a number of findings:

First, the TCJA caused domestic investment of firms with the mean tax change to increase by roughly 20% relative to firms experiencing no tax change. Second, the TCJA created large incentives for some U.S. multinationals to increase foreign capital, which rose substantially following the law change. Third, domestic investment also increases in response to foreign incentives, indicating complementarity between domestic and foreign capital in production. Fourth, the general equilibrium long-run effects of the TCJA on the domestic and total capital of U.S. firms are around 6% and 9%, respectively. Finally, in our model, the dynamic labor and corporate tax revenue feedback in the first 10 years is less than 2% of baseline corporate revenue, as investment growth causes both higher labor tax revenues from wage growth and offsetting corporate revenue declines from more depreciation deductions.

The results of the Trump corporate tax reform were more business investment, more growth, more wages for workers—and little impact on government revenue as lower corporate tax rates were offset by an expanding economy. Game, set, match.”

Responding to the study, William McBride and Alex Durante of the Tax Foundation elaborate on how lower corporate tax rates still generate voluminous receipts for the Treasury, even within the 10-year windows of Beltway budgeting:

“Regarding the TCJA’s impact on tax revenue, the study finds small dynamic effects within the 10-year budget window after accounting for increased economic activity. Tax revenues from labor increase due to the increased wage growth but are offset by a decline in corporate tax revenue particularly from bonus depreciation in the first few years after enactment. However, by year 10, dynamic corporate tax revenue gains begin to offset static corporate tax revenue losses while dynamic labor tax revenue reaches about 15 percent of baseline corporate tax revenue. This is sufficient to fully offset the static revenue losses from the corporate provisions by the end of the budget window.”

“These are the most convincing estimates of the response of investment to corporate tax rates that I’ve ever seen,” says Harvard’s Jason Furman, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration. “Taxes actually do matter…Companies that saw larger reductions in tax rates from the TCJA also experienced larger increases in investment in the years that followed…”

Then there is Stephen Moore’s recent Washington Examiner article titled, “It’s Official: Trump’s Tax Cuts Paid For Themselves”.

“The latest Congressional Budget Office report released earlier this month calculated that the federal government collected $4.9 trillion of federal revenue last year. This was up — ready for this? — almost $1.5 trillion since 2017, the year before the tax cuts became law. In other words, revenues were up 40% in five years. The evidence through the first three years of the tax cut finds that the share of taxes paid by the wealthiest 1% rose as well. So much for this being a tax giveaway for the rich.”

“In other words, there was a giant Laffer Curve effect from Trump’s tax cut. We got higher growth and higher tax payments with lower tax rates. This shouldn’t be a giant surprise. The same thing happened when Democratic President John F. Kennedy cut tax rates in the 1960s and when Republican President Ronald Reagan cut tax rates in the 1980s. Lower rates and more revenues.”

The above-mentioned evidence contradicts the statements by D-K which according to our reading of their article assumes little or no substitution effects. Economic theory suggests that if these substitution effects or supply side effects are significant, then the “revenues losses” generated by tax rate reductions will fall short of the static revenue estimates. If sufficiently large the substitution effects give rise to the possibility that a tax rate reduction could result in a long-run revenue gain. The results reported in the Freeman and Moore articles are consistent with this point of view, that the long-run impact of the substitution effects was significant and resulted in higher tax revenues.

The D-K document makes it clear that Bidenomics aims to meet several objectives: Social justice, DEI, the Green Agenda, and an industrial policy aimed at fostering these objectives. To do so, it will need additional tax revenues. Given D-K static revenue analysis, the increased revenue needs require a tax rate increase. The Biden administration will do this in several steps. The first step will be the easier one. The Biden administration will let the Trump personal income tax rates sunset. Even if the Republicans take both the House and Senate, they will not have a majority large enough to override a veto. Therefore, assuming a Biden reelection, the personal income tax rates will increase.

If the Democrats do not control the House and Senate, raising the corporate and personal income tax rates and or joining the global minimum tax compact will be a more difficult task. That will force the Biden administration to pursue non-legislative alternatives to these increases. Look for increased regulations and mandates as well as international side deals as substitutes for the inability to raise tax rates through the legislative process. Finally, the Supreme Court may very well rule that taxing unrealized gains is unconstitutional further damaging the Biden administration quest for revenues.

Importantly, the impact of the substitution effects generated by the Biden policies would result in a lower tax base and a smaller increase in revenues than those predicted by the static revenue analysis that D-K propose. If sufficiently large, the tax base shrinkage could lead to a long-run decline in revenues, leaving the government in a worse financial situation. That is why we say that substitution effects are perilous to ignore. Under these circumstances the revenues collected will be below projection and given the programmed spending that Bidenomics requires a larger budget deficit will ensue and an increasing public debt to GDP ratio.

The last point to make is that government spending is a key variable for Bidenomics. The reliance on Aggregate Demand management means that Bidenomics must maintain a high and possibly rising level of public spending. D-K argue that tax increases should be pay as you go while no constraint is imposed on government spending. We believe some sort of pay as you go spending restriction should also be enacted and our preference is for a simple rule – keep government spending growth to that of the sum of population plus inflation. This would keep the level of real public services constant and the revenues generated by the increases in productivity would then be used to retire the debt. We did this quite successfully with the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings legislation and Canada under the Harper administration had a similar successful outcome.

Here is where the Republicans come into play even if President Biden wins reelection. If the Republicans take over the House or Senate or both, they will be able to force the Biden administration into budget negotiations and hopefully correct Bidenomics tax and spend bias. In our opinion, the real message in Biden’s low approval rating is that Bidenomics as economic policy is increasingly being rejected by the American populace.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The information in this report was prepared by Timber Point Capital Management, LLC. Opinions represent TPCM’s and IPI’s opinion as of the date of this report and are for general information purposes only and are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally. IPI does not undertake to advise you of any change in its opinions or the information contained in this report. The information contained herein constitutes general information and is not directed to, designed for, or individually tailored to, any particular investor or potential investor.

This report is not intended to be a client-specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon.

This communication is provided for informational purposes only and is not an offer, recommendation, or solicitation to buy or sell any security or other investment. This communication does not constitute, nor should it be regarded as, investment research or a research report, a securities or investment recommendation, nor does it provide information reasonably sufficient upon which to base an investment decision. Additional analysis of your or your client’s specific parameters would be required to make an investment decision. This communication is not based on the investment objectives, strategies, goals, financial circumstances, needs or risk tolerance of any client or portfolio and is not presented as suitable to any other particular client or portfolio. Securities and investment advice offered through Investment Planners, Inc. (Member FINRA/SIPC) and IPI Wealth Management, Inc., 226 W. Eldorado Street, Decatur, IL 62522. 217-425-6340.

Recent Comments