We argue that the Global Minimum Tax and the Buy American Industrial Policy appear to contradict each other. The contradiction is as follows: On the one hand the Biden Administration is advocating a global minimum tax, a policy aimed at preserving the member countries’ tax base. Or as the Secretary of the Treasury put it, to prevent a race to the bottom. The global minimum tax aims to remove tax competition as a tool that some countries use to attract business and or capital through a business-friendly tax code, i.e., a simpler and lower tax rate. In 2021 Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen released the following statement endorsing the global minimum tax by G20 countries:

Today, every G20 head of state endorsed an historic agreement on new international tax rules, including a global minimum tax that will end the damaging race to the bottom on corporate taxation. It’s a critical moment for the US & the global economy. I congratulate President Biden on this important achievement.

This deal will remake the global economy into a more prosperous place for American business & workers. Rather than competing on our ability to offer lower rates, America will now compete on the skills of our people, our ideas, & our capacity to innovate — which is a race we can win.

At the same time, the Biden administration has also adopted an industrial policy with a strong dose of protectionism. The legislation includes a myriad of subsidies for a variety of industries that use labor unions. Then there are subsidies aimed at reducing the supply chain deficiencies manifested during the pandemic – the semiconductor industry immediately comes to mind. The idea behind these policies is that by attracting industries to produce in the US or regions nearby that have free trade agreement with the US, the dependency on supply chains located in foreign and potentially adversary localities will be reduced. In his most recent State of the Union President Biden described a series of policy initiatives of his administration:

Folks, I know I’ve been criticized for saying this, but I’m not changing my view. We’re going to make sure the supply chain for America begins in America…it’s totally consistent with international trade rules. Buy American has been the law since 1933. But for too long, past administrations — Democrat and Republican — have fought to get around it. Not anymore.

Tonight, I’m also announcing new standards to require all construction materials used in federal infrastructure projects to be made in America. I mean it. Lumber, glass, drywall, fiber-optic cable…And on my watch, American roads, bridges, and American highways are going to be made with American products as well.

Viewed from the national competition perspective, there appears to be an inherent contradiction in advocating for a global minimum tax while advocating for a protectionist industrial policy. The global minimum tax aims to reduce the tax competition and thus the benefits to relocating to the lower taxed localities. Yet the industrial policy and supply chain initiatives aim to attract companies to relocate in the US. The latter is precisely what lower tax rates at the individual state level do to attract companies to relocate within their borders by lowering their tax rates.

In contrast, the US plans to do the same by subsidizing the companies. Hence the difference being that one is using tax rate cuts while the other is using subsidies to achieve the same objective. Viewed this way one discourages mobility while the other encourages it. Another contradiction is that one is a global compact while the other may be viewed as a beggar thy neighbor competitive type of policy, a type of policy that the global tax is aiming to slowdown.

Taxes and Subsidies

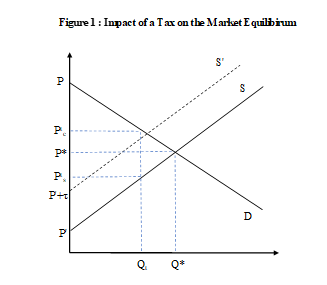

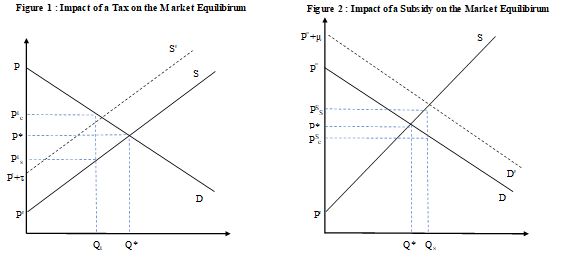

Absent any externalities a tax rate creates a wedge between the price paid by the consumer and the price received by the supplier. As such it alters the incentive structure of the economy. The tax increases the price paid by consumers to Ptc from P* thereby reducing the demand for the goods and services, see Figure 1. On the supply side, the tax reduces the price received by the producers to Pts from P*, thereby reducing the incentives to produce. With a lower demand and a lower quantity supplied, output will unambiguously decrease to Qt from Q*. The difference between the price paid by consumers, Ptc, and the price received by the producers, Pts, is nothing more than the tax. Figure 1 shows visually something that we already knew. The higher the tax rate, the lower the level of output and thus the tax base. Similarly, the lower the tax rate, the higher the level of output.

One can see the rationale for the global compact. The countries with the above average tax rates have a strong incentive to join or promote a compact. This way they protect their tax base that funds their projects.

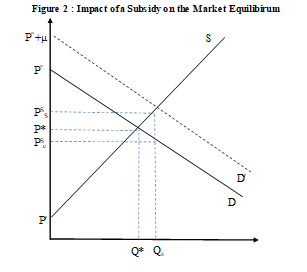

Similarly, also absent any externalities, a subsidy creates a wedge between the price paid by and received by the supplier. Again, the subsidy alters the incentive structure of the economy. The subsidy reduces the price paid by consumers to PSc from P* thereby increasing the demand for the goods and services, See Figure 2. On the supply side, the subsidy increases the price received by the producers to Pss from P*, thereby increasing the incentives to produce. With a higher demand and a higher quantity supplied, output will unambiguously increase to Qs from Q*. The difference between the price paid by consumers, PSc, and the price received by the producers, Pss, is nothing more than the subsidy. Figure 2 illustrates the rationale for the government subsidies and the basis for the Protectionist Industrial Policy. The greater the subsidy, the larger the increase in the production of the subsidized activity.

The conclusion reached in the previous paragraph raises an interesting issue – if the level of output is directly related to the amount of the subsidy, then why not subsidize everything, and produce more? The answer is simple. The subsidies are the equivalent of a negative tax. The taxes fill the Treasury’s coffers while the subsidies drain it. Hence, to expand the subsidy program the government needs additional revenues. Also, to the extent that there is a limit to the amount of tax revenues that the government can collect, the subsidy level will also be limited. Needless to say, in order to implement the BBB agenda, the government will need additional revenues. The President was not shy about it in his recent State of the Union speech:

That’s why I propose we quadruple the tax on corporate stock buybacks and encourage long-term investments. They’ll still make considerable profit…Let’s finish the job and close the loopholes that allow the very wealthy to avoid paying their taxes…But now, because of the law I signed, billion-dollar companies have to pay a minimum of 15 percent. God love them. Fifteen percent. That’s less than a nurse pays.

The President failed to mention that he is using a definition of income that is not the legal one used by the IRS or the National Income Accounts. President Biden’s definition of income includes unrealized capital gains. Then there is the fact that he is complaining that corporations and wealthy people are not paying their fair share, but he does not say that what they are doing is perfectly legal. Which raises a simple question, who wrote and approved the legislation that allowed corporations and people to reduce their tax rates? This is ironic coming from a president that is proposing to do just that to people who adopt his Green Energy Agenda. Fairness, like justice, should be blind and treat everyone equally. If we follow the president’s dictum to the extreme, the solution should be no exemptions which would lead to a flat and fair tax. A final point to make here is that in a system where economic agents maximize profits, taxes and subsidies lead to a suboptimal allocation of resources.

The Yellen Global Minimum Tax

Recently Janet Yellen, the Secretary of the Treasury, has proposed a Global Minimum Tax. Here is how the Secretary justified the Global Minimum Tax:

Today, every G20 head of state endorsed an historic agreement on new international tax rules, including a global minimum tax that will end the damaging race to the bottom on corporate taxation.

We could give the Secretary the benefit of the doubt and accept her statement. But what if we don’t? Let’s focus on the incentive structure and the after-tax rates of return from this policy. Domestically, it is quite possible that people facing steeper taxes may choose to work less and or invest less. Furthermore, if these factors of production are mobile, they will compare the taxes paid in their locality relative to other localities. Given the same income level, a tax differential that exceeds the costs of moving determines what happens – these factors will be better off migrating. The outmigration will erode the tax base of the high tax rate localities. If, to counteract the outmigration and shrinking tax base, the local authorities increase the tax rates to make up for the lower tax revenues, the outflow will accelerate. Ultimately the high tax rate locality ends up collecting less revenues and in a competitive world, the migration discipline will limit the taxing power and profligate spending of the local governments.

Is the Secretary attempting to protect these countries? In such a world, perfectly mobile factors will never be taxed at a tax rate higher than the lowest tax rate locality. The reason is simple, the mobile factors will relocate to the lowest tax rate locality. Obviously, this does not sit well with tax collectors from the higher tax rate localities. That is the high tax rate locality complaint, that they are losing the mobile factors and that reduces their tax base. That appears to be what the Secretary calls a race to the bottom. But looked at from another perspective, the so-called race to the bottom is a race to the top of after-tax income.

This gives us an interesting take on the externality concept. It seems that the government behavior is such that they perceive that the revenues belong to the government and that any collection below the maximum revenues reflects a leakage or externality. Since antitrust laws do not apply to tax collectors, they are free to collude. If the national tax collectors are able to come together, they may be able to form some sort of monopoly or cartel. But notice that the tax cartel does not worry about high tax rates, it only worries about the low tax rate. Why? Because the mobile factors tend to relocate to low tax rate areas. They do not tend to relocate to high tax rate areas. Hence the cartel will focus on the minimum tax rate and then will adopt measures aimed at reducing the cheating. Furthermore, as all cartels do, the members will try to maximize their tax revenues. Hence if the global minimum tax is enacted look for tax rates to go up.

The implementation issues faced by the high tax localities is how to convince or coerce the low tax localities to join the compact. As we know, theory suggests that collectively the localities have an incentive to get together to form the cartel while individually the members have an incentive to cheat while the other members adhere to the cartel rule. This means that the compact will have to develop an enforcement and monitoring mechanism to prevent the localities from “cheating” or diverging from the compact dictated minimum tax rate. Given the Biden administration has been a major force behind the minimum tax movement will the US become the chief watchdog in this endeavor?

The precursor to the Global Minimum Tax

In 2021 President Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. The package included $350 billion in aid for state and local governments, but the relief came with a catch. A provision added to the law at the last minute by Senate Democrats said that the funds could not be used directly or indirectly to offset a reduction in net tax revenue. To us it sounded like a first step towards a minimum tax.

An attempt to protect the tax base of high tax, i.e., blue states, and thus prevent the expansion of the low tax rate states, i.e., red states. The irony in all this is that the migration from high tax rate to low tax rate will not have a significant impact on the national averages, i.e., real GDP. Its major impact will be at the regional level. However,

the outflow from the high tax rate states has prompted the state tax authorities to aggressively pursue those leaving the state. In fact, some states, notably California among others, are considering imposing a wealth tax to those leaving the state. A tax and revenue measure that may not pass constitutional muster.

The empirical evidence and migration patterns suggest that low tax rates, not high tax rates, are the best way to attract income generation. But that poses a problem for the spendthrifts who need to protect their tax base to fund their profligate spending. That is why the Democrats in Congress, who share the same general vision and represent many of the areas in the blue states, voted to protect the high tax rate states’ tax base by adding a provision that if states lower their tax rates, they have to repay the funds to the Treasury.

But the low tax rate states did not stand still. A number of states filed lawsuits challenging the provision, forcing the U.S. Treasury Department to release guidance clarifying its stance. It allowed states to lower revenues by 1 percent of the baseline year without triggering the claw back. Treasury also allows organic growth to count toward offsetting tax reductions. But when all is said and done, the process seems very complicated, which makes it difficult for states to comply with. All of these components of the legislation and the Treasury guidance add complexity to the implementation of the legislation making it challenging for Treasury to enforce. In the end complicated laws lead to high enforcement costs and costly attempts to circumvent the restriction. The result being resources spent and wasted on enforcement, evasion, and avoidance, all of which tend to diminish the resources available to all.

The global minimum tax can be viewed as a successor to the restriction of lowering the tax at the state level. Based on public pronouncements and actions of a variety of government officials, one can make the case that these officials truly believe that there is a positive externality. Here is an excerpt from a document published by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD):

Domestic tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) due to multinational enterprises exploiting gaps and mismatches between different countries’ tax systems affects all countries. Developing countries’ higher reliance on corporate income tax means they suffer from BEPS disproportionately.

Business operates internationally, so governments must act together to tackle BEPS and restore trust in domestic and international tax systems. BEPS practices cost countries 100-240 billion USD in lost revenue annually, which is the equivalent to 4-10% of the global corporate income tax revenue.

Governments understand that businesses and people respond to incentives, and they move and relocate based in part on their after-tax income as we have argued. Yet the governments have a different perspective when it comes to tax revenues. They seem to believe that they won the tax base and thus the revenues. That profit shifting and base erosion is something to eliminate.

A free-market economist would argue that competition would force the countries to eliminate the erosion by matching the tax rate reduction. But these governments frown on it. The Treasury Secretary called it a “race to the bottom”. Instead of lowering their tax rates, these governments and other organizations prefer to erect tax rate cut barriers to protect the tax base of the higher and rising tax rate states.

The global minimum tax reduces the downside of a tax rate increase and collectively it increases the incentives for all localities in the compact to collectively increase their tax rates. But why? To us the short answer is to think in terms of who owns the revenues. Is it the private sector or is it the government? Who is the residual claimant? For a free market economist, the answer is clear, but for a dirigiste who advocates state control of economic resources, not so much. For a dirigiste, it is the government who owns the revenues generated by corporations and individuals, and the more they collect the more they can direct.

In short, the global minimum tax rules will add complexity and increase the compliance costs and will not end the tax competition among countries. It will induce a waste of resources devoted to avoidance and evasion. Contrary to the basic premise of the global minimum tax, competition can be a good thing by nudging tax authorities toward more economically efficient forms of taxation.

Beggar Thy Neighbor industrial policy

As referenced earlier, President Biden’s State of the Union speech reiterated his commitment to a protectionist industrial policy using taxes and subsidies as a key component of his Build Back Better (BBB) industrial policy.

Since the subsidies are a drain on the revenues of the Treasury, in order to finance the increased subsidies additional revenues will be required, i.e, higher tax rates, such as the quadrupling of the tax on stock repurchases as well as arguing for a higher income tax rate using a novel definition of income that includes unrealized capital gains. However, several legal experts believe that the definition the president proposes can be construed as a wealth tax and that is likely to be unconstitutional. Figures 1 and 2, revisited below, can be used to illustrate the possible effects of the tax-and-subsidy industrial policy.

As before, Figure 1 shows that a tax increase leads to a lower output of the taxed activity. A similar result can also be replicated by imposing a moratorium on production or a quota that reduces the output to Qt form Q*. In contrast, as shown in Figure 2, a subsidy leads to a higher output of the subsidized activity to Qs form Q*. Hence in simple terms the subsidy-tax instruments play the roles of the carrot, i.e., subsidies, and the stick, i.e., taxes. Government, with a judicious application of the carrot and stick, will be able to design an industrial policy that “guides” the economy in the direction that it favors.

The conflicting industrial policies may be justified in one of two ways. The first presumes that the market will eventually drive the global economy to the desired outcome. In this case there is no external effect, and the industrial policy merely accelerates the speed of adjustment to the long run equilibrium. The second possibility is due to some sort of externality whereby the government believes that the costs of the policies are not fully incorporated in market prices and as a result it takes action to eliminate or at least reduce the external effects. Either way these two possibilities give rise to an industrial policy such as ‘Buy American’, as well as the Green Energy Agenda being pushed by the EU and US governments.

But if the governments believe that there is a global externality, the proper solution is a coordinated effort by all of the governments in the world. Only then can the distortion or external effect be eliminated. If a government goes it alone, all that government can hope for is a second-best solution that approximates the first best within the constraint faced by the local economy. Then there is the issue of the likely success of an industrial policy.

The Biden administration is betting that it can pick the winners and the least expensive glide path to the long run equilibrium, the end point that they foresee. But what if they are wrong? The historical experience shows that the government is not very good at picking winners. Another potential problem is that the subsidized companies will become political hostages in the green trade wars. The industrial policy, with their subsidies and border taxes will lead to a misallocation of investment. In the end it will result in higher costs and slower growth. It risks returning the world to the bad old days of nationalist production, less competition, and higher costs for consumers. Of course, that is not what the Biden administration is counting on.

Furthermore, the rest of the world is likely to respond, and the result could be a beggar thy neighbor tit-for-tat tax industrial policy. The countries will respond by either imposing countervailing duties or by developing their own protectionist or nationalistic industrial policy. The tit-for-tat could easily develop into the race to the bottom that Secretary Yellen worries so much about. Yet there are a few differences between the tax rates and the industrial policy tit-for-tat.

The tax rate competition at least results in lower tax rates for the global economy. Free market economists believe that absent government interference the private sector is pretty good at assessing risks and solving its problems as directed by the profit motive. Hence, according to this view the ideal policy would be for the government to get out of the way and adopt a broad low tax rate environment and allow the private sector to relocate and produce wherever it is more attractive. But that requires that the government abandon its dirigisme. Unfortunately, this is something that the Biden administration is not willing to allow.

Instead, the Biden administration has chosen an industrial policy based on subsidies in order to attract and stimulate the relocation of industries and protection of domestic industries and unions. The rest of the world will be forced to respond in kind. Given the equivalence that we have already established, the subsidies are nothing more than negative tax rates. Hence an expansion of the subsidy regime will increase the revenue needs of the different national treasuries which will force these countries to raise their tax rates. If the revenues do not keep up with subsidies, the fiscal situation of these economies will deteriorate and increase the likelihood not only of a national fiscal crisis and an economic recession, but also a global one.

Policy Schizophrenia?

By favoring a global minimum tax the signatories are attempting to limit the tax competition among nations. Under a competitive system, all else the same, the mobile factors will migrate to the lowest tax rate locality thereby reducing the tax base and revenues of the higher tax rate localities while increasing the tax base of lower tax localities. If the base increase is sufficiently large it may even increase the tax take of the low tax rate countries. But that is not all.

The lower tax rates not only attract foreign capital and labor, it also increases the incentives to work save and invest by the locals. The end result being an increase in economic activity in the low tax rate localities and a reduction of economic activity in the high tax rate localities. Hence from a simple revenue perspective, the countries with an above average tax rate will have a strong incentive to join the global minimum tax compact. Sadly, the US is one of the leaders.

The US is willing to adopt a subsidy strategy, i.e., a negative tax strategy, to attract and stimulate relocation to the US presumably to reduce supply chain dependencies and to bring manufacturing back home. All laudable objectives. The only issue is that such policies are inconsistent with the rationale behind the minimum global tax. The latter is supposed to stop a “race to the bottom” while the Biden industrial policy is likely to fuel a beggar thy neighbor industrial policy that could easily develop into its own race to the bottom.

Worse yet, if the industrial policy does not deliver, the world will be worse off. This obviously raises the question of why do it? What motivation or ideal could push the Biden administration to pursue contradictory policies? Our answer is that the pursuit of the BBB policies the administration is willing to bet the farm, better said, the world, that its economic model will deliver as they expect. And as such it is willing to do anything in pursuit of these objectives. But they do not appear to have considered the possibility that they could be wrong. This does not mean that we doubt the sincerity of the administration. We simply doubt that they will be able to accomplish what they are setting out to do and how they are going about it.

Simply put, the race to the bottom could bankrupt some national treasuries if they do not deliver the growth. All of this suggests that the protectionist industrial policy could be quite damaging to the public finances and ultimately result in a negative sum game among the national economies. In fact, these were the same worries of the US Treasury Secretary when she advocated for a global minimum tax.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The information in this report was prepared by Timber Point Capital Management, LLC. Opinions represent TPCM’s and IPI’s opinion as of the date of this report and are for general information purposes only and are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally. IPI does not undertake to advise you of any change in its opinions or the information contained in this report. The information contained herein constitutes general information and is not directed to, designed for, or individually tailored to, any particular investor or potential investor.

This report is not intended to be a client-specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon.

This communication is provided for informational purposes only and is not an offer, recommendation, or solicitation to buy or sell any security or other investment. This communication does not constitute, nor should it be regarded as, investment research or a research report, a securities or investment recommendation, nor does it provide information reasonably sufficient upon which to base an investment decision. Additional analysis of your or your client’s specific parameters would be required to make an investment decision. This communication is not based on the investment objectives, strategies, goals, financial circumstances, needs or risk tolerance of any client or portfolio and is not presented as suitable to any other particular client or portfolio. Securities and investment advice offered through Investment Planners, Inc. (Member FINRA/SIPC) and IPI Wealth Management, Inc., 226 W. Eldorado Street, Decatur, IL 62522. 217-425-6340.

Recent Comments